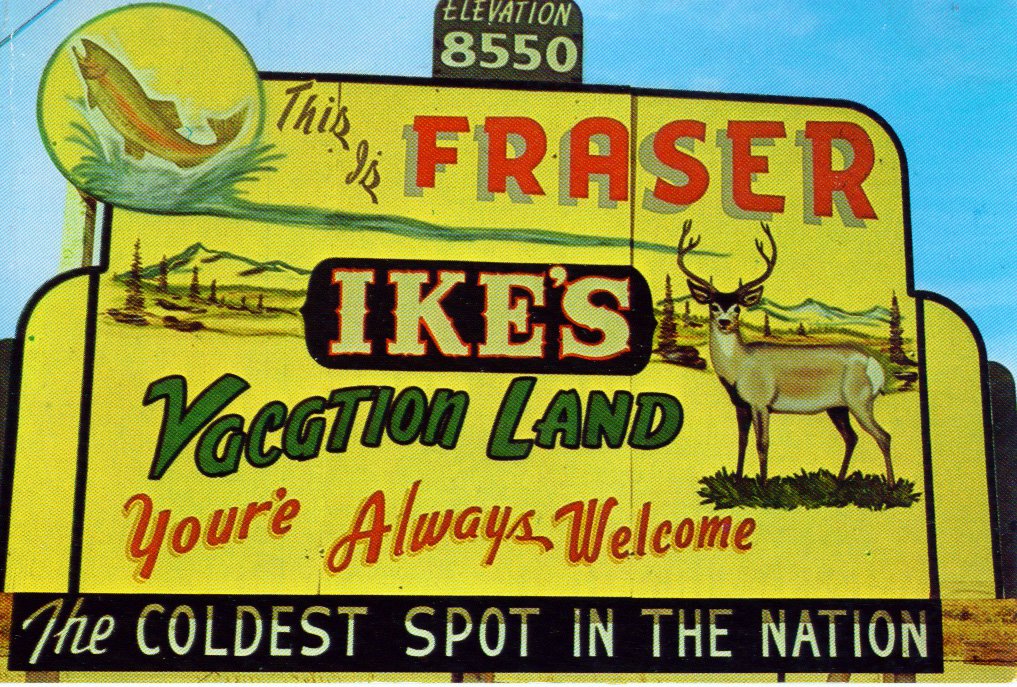

THINKING INSIDE THE ICEBOX: FRASER, COLORADO

Stories, commentary, history, and musings about my hometown of Fraser, Colorado. Not really a blog so much as a collection of writings that I add to now and then.

My Favorite Mountains: The Divide

Note: this was published in the August 2010 issue of the Mountain Gazette.

The mountains I love the most consist of a stretch of the continental divide that runs between the Northern Colorado’s Arapaho Peaks and Berthoud Pass. It is a modest chunk of the Front Range, eclipsed in scenery by the Indian Peaks to the north, and in elevation by a slew of well-known 14ers to the south. My mountains are not jagged or very rugged —they have been described as “rolling gray elephants”, and some sections barely top 11,000 feet—but they hold sway over me for other reasons.

I was fortunate enough to spend my childhood in the shadow of these mountains and much of their impact on me was caused by the countless hours I spent just looking at them. I watched as they brewed a thousand dark thunderstorms that crept down their piney flanks and drenched our valley with summer rains. I watched as blizzards swallowed the whole range for days at a time, then watched as the weather broke and gales blew banners of snow off the peaks and into the cold blue sky. I watched the alpenglow fade in and out, the lightning flash silently behind them for hours on end, and the tundra turn from summer green to autumn gold to dead brown to dusted with snow—midsummer to early winter in just a few short weeks. Over time every crag, chute, outcrop, and cliff was eternally seared onto my brain, and each of the mountains that make up that ridge stares at me with an expression that I know well.

Eventually I entered these mountains, first with family, then with friends, creating memories that unfold within and atop this stretch of the Great Divide: picking wild raspberries with my grandparents along Ranch Creek; driving up in the fall to listen to the elk bugle; camping in a canvas tent with my Dad just once before he walked away from fatherhood; drinking my very first beer (Coors from a keg) at age 12 at the annual Mt. Epworth summer ski race; catching a glimpse of my first bear up Jim Creek; backpacking for the first time of my life up Cabin Creek; hiding from a fierce lightning storm in the boulder piles near Devil’s Thumb; clawing my way up James Peak after the death of my Grandfather because I didn’t know what else to do.

Much of this range is now protected wilderness, but it is far from untouched. Cars and snowmobiles can crest the ridge from both sides of the divide, and every pristine stream that runs west off of those mountains is quickly dammed and diverted under the mountains and into the thirsty gullet of the Denver Water Board. High above the timberline, one can see long stacks of lichen-covered stone that early natives built to funnel animals towards waiting hunters, and Ute or Arapaho teepee rings are visible in at least one sub-alpine meadow. There are remains of the first wagon road chiseled across this part of the divide around 1870, mounds of rusted tin cans and broken bottles that reveal logging camps of yore, and a few bits of mining wreckage left by prospectors who found no trace of mineral wealth so tantalizingly close to the lodes discovered only a few miles away in Central City, Empire, Caribou.

But the most striking signs of humanity all have to do with the railroad—testament to the power of shovels and dynamite—that was pushed over Rollins pass in 1904, including the crumbling foundation of a mountaintop hotel (and bits of wire that anchored it to the windswept tundra), petrified lumber and rusted square nails that were once a miles long snow shed that sheltered trains from 60 foot snowdrifts, and a series of intact wooden trestles that still span ravines and enabled the trains to wind their way gradually down into the valley. Below one set of these trestles lay the twisted iron remains of a train that was swept off the tracks by an avalanche and smashed upon a field of boulders at the foot of the mountain. As a kid, the sight of that wreckage sent shivers down my spine every time I saw it, for it symbolized the brutal and destructive power of the mountains in winter, a force far stronger than us.

Like my boyhood home, the place where I live now is blessed with epic mountains, and I have spent thousands of hours exploring them, but I will never be connected to them in the same way. Where once I simply saw MOUNTAIN—brooding, menacing, all powerful, full of mystery—my knowledge now burdens me with perceptions of watershed, bioregion, topographic lines, a threatened chunk of earth, a place trampled by hooves, burdened by fire suppression, sprinkled with nuclear fallout, layered with history both geologic and historical. Were I to see my childhood mountains for the first time now, their humble stature and the sizable human footprint they carry would likely lead me to view them as inferior to bigger and less impacted mountains elsewhere. Suffice to say that I now know what’s on the other side of the mountain, any mountain, or at least that’s what I tell myself, and this knowledge (too many books, too much chattering brain, not enough WATCHING) has both widened and narrowed the lens through which I see the world, including mountains, and there is no going back.

The mountains I love the most consist of a stretch of the continental divide that runs between the Northern Colorado’s Arapaho Peaks and Berthoud Pass. It is a modest chunk of the Front Range, eclipsed in scenery by the Indian Peaks to the north, and in elevation by a slew of well-known 14ers to the south. My mountains are not jagged or very rugged —they have been described as “rolling gray elephants”, and some sections barely top 11,000 feet—but they hold sway over me for other reasons.

I was fortunate enough to spend my childhood in the shadow of these mountains and much of their impact on me was caused by the countless hours I spent just looking at them. I watched as they brewed a thousand dark thunderstorms that crept down their piney flanks and drenched our valley with summer rains. I watched as blizzards swallowed the whole range for days at a time, then watched as the weather broke and gales blew banners of snow off the peaks and into the cold blue sky. I watched the alpenglow fade in and out, the lightning flash silently behind them for hours on end, and the tundra turn from summer green to autumn gold to dead brown to dusted with snow—midsummer to early winter in just a few short weeks. Over time every crag, chute, outcrop, and cliff was eternally seared onto my brain, and each of the mountains that make up that ridge stares at me with an expression that I know well.

Eventually I entered these mountains, first with family, then with friends, creating memories that unfold within and atop this stretch of the Great Divide: picking wild raspberries with my grandparents along Ranch Creek; driving up in the fall to listen to the elk bugle; camping in a canvas tent with my Dad just once before he walked away from fatherhood; drinking my very first beer (Coors from a keg) at age 12 at the annual Mt. Epworth summer ski race; catching a glimpse of my first bear up Jim Creek; backpacking for the first time of my life up Cabin Creek; hiding from a fierce lightning storm in the boulder piles near Devil’s Thumb; clawing my way up James Peak after the death of my Grandfather because I didn’t know what else to do.

Much of this range is now protected wilderness, but it is far from untouched. Cars and snowmobiles can crest the ridge from both sides of the divide, and every pristine stream that runs west off of those mountains is quickly dammed and diverted under the mountains and into the thirsty gullet of the Denver Water Board. High above the timberline, one can see long stacks of lichen-covered stone that early natives built to funnel animals towards waiting hunters, and Ute or Arapaho teepee rings are visible in at least one sub-alpine meadow. There are remains of the first wagon road chiseled across this part of the divide around 1870, mounds of rusted tin cans and broken bottles that reveal logging camps of yore, and a few bits of mining wreckage left by prospectors who found no trace of mineral wealth so tantalizingly close to the lodes discovered only a few miles away in Central City, Empire, Caribou.

But the most striking signs of humanity all have to do with the railroad—testament to the power of shovels and dynamite—that was pushed over Rollins pass in 1904, including the crumbling foundation of a mountaintop hotel (and bits of wire that anchored it to the windswept tundra), petrified lumber and rusted square nails that were once a miles long snow shed that sheltered trains from 60 foot snowdrifts, and a series of intact wooden trestles that still span ravines and enabled the trains to wind their way gradually down into the valley. Below one set of these trestles lay the twisted iron remains of a train that was swept off the tracks by an avalanche and smashed upon a field of boulders at the foot of the mountain. As a kid, the sight of that wreckage sent shivers down my spine every time I saw it, for it symbolized the brutal and destructive power of the mountains in winter, a force far stronger than us.

Like my boyhood home, the place where I live now is blessed with epic mountains, and I have spent thousands of hours exploring them, but I will never be connected to them in the same way. Where once I simply saw MOUNTAIN—brooding, menacing, all powerful, full of mystery—my knowledge now burdens me with perceptions of watershed, bioregion, topographic lines, a threatened chunk of earth, a place trampled by hooves, burdened by fire suppression, sprinkled with nuclear fallout, layered with history both geologic and historical. Were I to see my childhood mountains for the first time now, their humble stature and the sizable human footprint they carry would likely lead me to view them as inferior to bigger and less impacted mountains elsewhere. Suffice to say that I now know what’s on the other side of the mountain, any mountain, or at least that’s what I tell myself, and this knowledge (too many books, too much chattering brain, not enough WATCHING) has both widened and narrowed the lens through which I see the world, including mountains, and there is no going back.

Trains

There’s something otherworldly about a train—a mysterious power beyond ordinary horsepower. As a kid, I would lay in my bed listening for the deep rumble of the midnight freights, a sound that I felt in my bones long before I could hear it. Then the whistle would pierce the air and echo across the frozen valley, a mournful cry in the night. I’ve heard lots of folks, especially the newcomers, complain about the trains interrupting their sleep, but for me they have always been soothing. Like an old clock striking the hour, or church bells ringing on a Sunday morn. Often unnoticed but always there, countless tons of steel hissing and squealing through the middle of town at all hours of the day and night, through blizzards and sunshine, providing a century of background music as the generations of Fraser families live out their lives.

The first train came through Fraser in 1904 via Rollins pass, a small gap in the Front Range of the Rockies a little over 11,000 feet high. Known to engineers as “The Hill”, this amazing bit of road building (as in RAILroad) consisted of more than 30 tunnels and an elaborate series of loops and trestles designed to get trains up and over the continental divide on a year round basis. The purpose was two-fold: First, tycoons wanted access to the resources of northwest Colorado, such as beef, timber and coal, and second, Denver was at the end of the line and feared for its future lest it be eclipsed by Cheyenne to the north or Pueblo to the south, growing cities situated on cross-country rails. The only solution was to blaze a twin steel trail up and over the mountains as soon as possible, so that’s what happened.

Despite the hardships, such as avalanches, tunnel fires and 40 foot snowdrifts, the railroad was remarkably efficient, delivering newspapers, mail, and wooden crates full of fresh bread to all the towns between Fraser and Craig, where the line ended. During the winter the dirt road of Berthoud pass (later US 40) would be inundated by snow, remaining that way until late spring when crews would shovel it out by hand. This meant that for up to 6 straight months the train was the only way in or out of the snowbound valley, unless you wanted to snowshoe. Catch the eastbound at 2 am and if all went well you’d be in Denver by 8:30 that morning, just in time to catch the trolley to high school, which my Grandmother did a few times.

Eventually Rollins pass was bypassed by the Moffat Tunnel, a seven mile passage that went under the great divide, and a few years later the Dotsero cutoff was completed, which connected the railroad to Pacific bound rails and put Fraser right on a true transcontinental railroad. Around this time the “Victory Highway” was paved and made into U.S. Highway 40, and modern snowplows allowed the road to stay open year-round, more or less. By the 1970’s, when I was growing up in Fraser, local service was obsolete, and rail traffic consisted mostly of the long haul freights and coal trains that one sees today.

There were still remnants of the glory days to be seen however, such as the California Zephyr. Three or four times a week this gem would pass through town en route to Chicago or San Francisco, gracing the valley with streamlined orange locomotives and a string of glassy silver dome cars, a real blast of 1950’s sleekness and space age style. Another glimpse of railroads past were the old stockyards next to the siding, a whole mess of rotten and splintered boards with gates that still opened and closed. Lots of rusty nails too. My mom wouldn’t let me near the place, telling me that they were old and rickety when she was a kid, but most of the rest of the kids in town spent plenty of time there.

My first ‘hike’ was a walk on the tracks with Grandma. She showed me the trail that used to parallel the rails, and then we walked up towards the cemetery, stepping on the crossties and avoiding the globs of tar. The crunch of black cinders underfoot, the old spikes scattered about, the smell of creosote...everything having to do with the railroad seemed filthy, but in a good way. We got to the trestle and turned back cause you never knew if a train might come out of those woods.

Back then all the engines were of the Rio Grande Railroad, black with orange or yellow lettering, sometimes 10 or more locomotives to a train, with a caboose at the end. The Rio Grande locomotives are rare now that Union Pacific owns the line, and cabooses disappeared in the mid-1980’s, but back then there was always one, sometimes two or three, usually orange. Often these were followed by a set of two “pusher” engines which would help the long coal trains reach the apex of the line at the Moffat Tunnel. These are obsolete now as well; I guess the new locomotives are more powerful.

The bulk of a train consisted of the usual cargo: tankers full of oil or ammonia or who knows what else, black or white but always stained with unknown grime; gondolas laden with woodchips or stacks of lumber from the local sawmill; grain hoppers and boxcars covered with graffitti; autocarriers laden with fresh Detroit iron and glass, and plenty of piggy back semi truck trailers, with the UPS and postal service trailers always at the very end. But most of the time it was King Coal, as mile long strings of 100 or more coal hoppers passed through town from remote Colorado strip mines to the power plants and steel mills of Front Range cities: 10 trains a day, 6 days a week, for the past 3 decades or more.

Every so often a non-Rio Grande engine would appear, causing some excitement: Union Pacific, the green of Burlington Northern, or the grey and red of the Santa Fe railroad. Much of my youth took place during the height of the Reagan era cold war, and about once a month we were reminded of this fact when a military train would pass through town. No cannons or tanks, but plenty of jeeps, troop transports, fuel trucks, trailers and heavy equipment, all of it painted up in camoflauge or olive drab like GI Joe toys. It was a strategic shuffling of war implements, conjuring apocalyptic images of doom which frightened yet intrigued me all at once.

The best and rarest occasion of all was the Ringling Brothers Barnum and Bailey Circus Train that would pass through each fall on its way to Denver. For days before it actually appeared, every whistle would divert the entire school’s attention away from lessons as we peered out in unison for a glimpse of what just might be the circus train. But luckily it always came in the evening. We would park up near the main crossing with dozens of other folks in the know and wait. Soon it would appear, a series of Rio Grande engines pulling the painted train. There were no open cages or anything like that, but it possessed an aura of timeless excitement comparable to a gypsy wagon of old.

Despite my love for trains, they were often the target of our bored mischief. My first taste of train track delinquency took place one day after kindergarten. At this point there was not yet an Amtrack nor a train station, and both sides of the tracks through town were lined with enough big willows to provide hiding places galore. The elder Klancke girl and I took sticks and smeared tar on the rails, hoping to either stop the train or cause it to slide like in the movies. We tried many times, but were always disappointed (and secretly relieved) when the train just rolled on by. In the end, all we ended up doing was permanently staining our clothes with industrial grade tar—only gasoline would get them clean again. Eventually, hoping to derail a train, we started putting rocks on the tracks, but they would simply be shattered by the sheer weight of the engines. Rumor had it that a plain old quarter could derail a train, but none of the 20 bucks or so worth of coins we tried over the years managed to net us a train wreck.

The first trackside fort I ever saw was on the other, bad side of the tracks. The collective gang of Morrows, Murrays and Tuckers had built an elaborate rail tie bulwark designed to protect them from the buckshot and salt pellets that caboose men were rumored to shoot at hoodlums who dared to throw rocks at the trains. Soon we on the eastside had our own forts, starting with some hay bales right next to the old depot building. But this was right on the road, dangerously close to adult supervision, so we moved 100 yards up the tracks near what would later become the Divide condos. This wasn’t too far from my Grandparent’s house, which gave us easy access to my Grandad’s gardening implements to trim willow branches or transplant weeds to help hide our forts. Once they were built, we would gather up rocks for ammunition, and then we would wait.

And wait.

And wait some more, now and then checking the tracks for a hint of rumble or peering into the switch lights for any color, red or green, for either meant that something was on the line. Soon that tell tale rumble sent us rushing to our designated spots, where we prepared to attack the train. The anticipation was intense, and the fear factor would build as the locomotives got closer and the ground started to shake. Suddenly the enemy was upon us and we would all let go with a flurry of cinders and stones...rocks shattering harmlessly against 40-ton coal cars. Soon we were using slingshots and bb guns, which were small potatoes compared to the sight of exploding glass when 2 siblings let loose with 12 gauge shotguns on a trainload of shiny new automobiles…my older cousins, who shall remain nameless, did this once back in the early 60’s.

There were still a few hobos riding the rails back then. Once a shirtless and bald tattooed giant gave us a wave from his dangerous resting place between coal cars as we walked the summer tracks to baseball practice. He had just come through the tunnel and was stained with soot. Another time, an evening game of tag was interrupted as we rode our bikes up to the tracks behind the new school by the St. Louis Creek trestle to throw rocks at a passing freight. Gondolas, tanker cars...suddenly I saw a group of Mexican hobos lounging in an open box car just as a rock bounced off the car right next to their heads with a CLANG! We fled in a panic, fearful that they were going to jump off and hunt us down.

While the trains were a constant source of amusement and games, there was always an element of danger and death as well. Stories of getting sucked under a fast moving freight turned out to be false, but the story of my granduncle losing an arm when he fell across the path of an oncoming train was true. Once, in the first grade, a chemical leak in a tank car forced us to spend recess indoors, which led to a grand game of school wide dodge ball in the tiny gymnasium. Years later an Amtrack derailed in the Fraser Canyon, resulting in no deaths, but giving us a rare spot on the national news. The worst incident occured in the mid-80’s when a train smashed into a car up at the 4 bar 4 road crossing one frigid winter night. My step dad was a tow truck driver and was one of the first on the scene. They looked everywhere for the body, assuming that it had been jettisoned from the vehicle upon impact, but they simply couldn’t find it. Turns out she was still in the mangled remains of the automobile, dead silent in the midst of a frantic search effort.

Incidents like this were rare, however, and most of the time the trains passed through town without fanfare or disaster, just like they have for the last 100 years. The rails provide a sort of long term calendar for Fraserites to guide their lives by: trains throughout the day and night are like the hours on a clock; the Amtrack is like the rising and setting of the sun (but don’t set your watch by it!); the annual circus train was like a new year’s celebration; and the ski train was the harbinger of winter and hordes of tourists. Longer cycles and stages of life were mirrored by the crews of gandy dancers that would come through twice in a decade to replace the rails, sleeping at the siding in bunkhouse cars next to the bizarre array of machinery unique to the railroad.

The railroad looms large in the history of Fraser, for it brought sawmills, settlers, and civilization to the cold, quiet valley, and led to the very creation of the town itself. These days, for better or for worse, it carries the seemingly endless tons of coal necessary to power our computers, lights and teevees, and will, in the future, surely play a larger role in the transport of both freight and people. Certainly the railroad is big and important, but it’s the small things that have a hold on my heart: the way the rail sinks and flexes as a loaded coal car passes over it; the squeals and squeaks and occasional CLUNK CLUNK CLUNK as one of the flatwheelers passes by; the flashing lights and clanging bells of the crossing gates; the lingering hiss of the rails right after the last car goes by; walking the thousand mile-long balance beam on the way to little league games and elementary school, and, of course, the sound of the whistle at night. Sure, the mountains are the soul of my Fraser, but the train is its beating heart.

The first train came through Fraser in 1904 via Rollins pass, a small gap in the Front Range of the Rockies a little over 11,000 feet high. Known to engineers as “The Hill”, this amazing bit of road building (as in RAILroad) consisted of more than 30 tunnels and an elaborate series of loops and trestles designed to get trains up and over the continental divide on a year round basis. The purpose was two-fold: First, tycoons wanted access to the resources of northwest Colorado, such as beef, timber and coal, and second, Denver was at the end of the line and feared for its future lest it be eclipsed by Cheyenne to the north or Pueblo to the south, growing cities situated on cross-country rails. The only solution was to blaze a twin steel trail up and over the mountains as soon as possible, so that’s what happened.

Despite the hardships, such as avalanches, tunnel fires and 40 foot snowdrifts, the railroad was remarkably efficient, delivering newspapers, mail, and wooden crates full of fresh bread to all the towns between Fraser and Craig, where the line ended. During the winter the dirt road of Berthoud pass (later US 40) would be inundated by snow, remaining that way until late spring when crews would shovel it out by hand. This meant that for up to 6 straight months the train was the only way in or out of the snowbound valley, unless you wanted to snowshoe. Catch the eastbound at 2 am and if all went well you’d be in Denver by 8:30 that morning, just in time to catch the trolley to high school, which my Grandmother did a few times.

Eventually Rollins pass was bypassed by the Moffat Tunnel, a seven mile passage that went under the great divide, and a few years later the Dotsero cutoff was completed, which connected the railroad to Pacific bound rails and put Fraser right on a true transcontinental railroad. Around this time the “Victory Highway” was paved and made into U.S. Highway 40, and modern snowplows allowed the road to stay open year-round, more or less. By the 1970’s, when I was growing up in Fraser, local service was obsolete, and rail traffic consisted mostly of the long haul freights and coal trains that one sees today.

There were still remnants of the glory days to be seen however, such as the California Zephyr. Three or four times a week this gem would pass through town en route to Chicago or San Francisco, gracing the valley with streamlined orange locomotives and a string of glassy silver dome cars, a real blast of 1950’s sleekness and space age style. Another glimpse of railroads past were the old stockyards next to the siding, a whole mess of rotten and splintered boards with gates that still opened and closed. Lots of rusty nails too. My mom wouldn’t let me near the place, telling me that they were old and rickety when she was a kid, but most of the rest of the kids in town spent plenty of time there.

My first ‘hike’ was a walk on the tracks with Grandma. She showed me the trail that used to parallel the rails, and then we walked up towards the cemetery, stepping on the crossties and avoiding the globs of tar. The crunch of black cinders underfoot, the old spikes scattered about, the smell of creosote...everything having to do with the railroad seemed filthy, but in a good way. We got to the trestle and turned back cause you never knew if a train might come out of those woods.

Back then all the engines were of the Rio Grande Railroad, black with orange or yellow lettering, sometimes 10 or more locomotives to a train, with a caboose at the end. The Rio Grande locomotives are rare now that Union Pacific owns the line, and cabooses disappeared in the mid-1980’s, but back then there was always one, sometimes two or three, usually orange. Often these were followed by a set of two “pusher” engines which would help the long coal trains reach the apex of the line at the Moffat Tunnel. These are obsolete now as well; I guess the new locomotives are more powerful.

The bulk of a train consisted of the usual cargo: tankers full of oil or ammonia or who knows what else, black or white but always stained with unknown grime; gondolas laden with woodchips or stacks of lumber from the local sawmill; grain hoppers and boxcars covered with graffitti; autocarriers laden with fresh Detroit iron and glass, and plenty of piggy back semi truck trailers, with the UPS and postal service trailers always at the very end. But most of the time it was King Coal, as mile long strings of 100 or more coal hoppers passed through town from remote Colorado strip mines to the power plants and steel mills of Front Range cities: 10 trains a day, 6 days a week, for the past 3 decades or more.

Every so often a non-Rio Grande engine would appear, causing some excitement: Union Pacific, the green of Burlington Northern, or the grey and red of the Santa Fe railroad. Much of my youth took place during the height of the Reagan era cold war, and about once a month we were reminded of this fact when a military train would pass through town. No cannons or tanks, but plenty of jeeps, troop transports, fuel trucks, trailers and heavy equipment, all of it painted up in camoflauge or olive drab like GI Joe toys. It was a strategic shuffling of war implements, conjuring apocalyptic images of doom which frightened yet intrigued me all at once.

The best and rarest occasion of all was the Ringling Brothers Barnum and Bailey Circus Train that would pass through each fall on its way to Denver. For days before it actually appeared, every whistle would divert the entire school’s attention away from lessons as we peered out in unison for a glimpse of what just might be the circus train. But luckily it always came in the evening. We would park up near the main crossing with dozens of other folks in the know and wait. Soon it would appear, a series of Rio Grande engines pulling the painted train. There were no open cages or anything like that, but it possessed an aura of timeless excitement comparable to a gypsy wagon of old.

Despite my love for trains, they were often the target of our bored mischief. My first taste of train track delinquency took place one day after kindergarten. At this point there was not yet an Amtrack nor a train station, and both sides of the tracks through town were lined with enough big willows to provide hiding places galore. The elder Klancke girl and I took sticks and smeared tar on the rails, hoping to either stop the train or cause it to slide like in the movies. We tried many times, but were always disappointed (and secretly relieved) when the train just rolled on by. In the end, all we ended up doing was permanently staining our clothes with industrial grade tar—only gasoline would get them clean again. Eventually, hoping to derail a train, we started putting rocks on the tracks, but they would simply be shattered by the sheer weight of the engines. Rumor had it that a plain old quarter could derail a train, but none of the 20 bucks or so worth of coins we tried over the years managed to net us a train wreck.

The first trackside fort I ever saw was on the other, bad side of the tracks. The collective gang of Morrows, Murrays and Tuckers had built an elaborate rail tie bulwark designed to protect them from the buckshot and salt pellets that caboose men were rumored to shoot at hoodlums who dared to throw rocks at the trains. Soon we on the eastside had our own forts, starting with some hay bales right next to the old depot building. But this was right on the road, dangerously close to adult supervision, so we moved 100 yards up the tracks near what would later become the Divide condos. This wasn’t too far from my Grandparent’s house, which gave us easy access to my Grandad’s gardening implements to trim willow branches or transplant weeds to help hide our forts. Once they were built, we would gather up rocks for ammunition, and then we would wait.

And wait.

And wait some more, now and then checking the tracks for a hint of rumble or peering into the switch lights for any color, red or green, for either meant that something was on the line. Soon that tell tale rumble sent us rushing to our designated spots, where we prepared to attack the train. The anticipation was intense, and the fear factor would build as the locomotives got closer and the ground started to shake. Suddenly the enemy was upon us and we would all let go with a flurry of cinders and stones...rocks shattering harmlessly against 40-ton coal cars. Soon we were using slingshots and bb guns, which were small potatoes compared to the sight of exploding glass when 2 siblings let loose with 12 gauge shotguns on a trainload of shiny new automobiles…my older cousins, who shall remain nameless, did this once back in the early 60’s.

There were still a few hobos riding the rails back then. Once a shirtless and bald tattooed giant gave us a wave from his dangerous resting place between coal cars as we walked the summer tracks to baseball practice. He had just come through the tunnel and was stained with soot. Another time, an evening game of tag was interrupted as we rode our bikes up to the tracks behind the new school by the St. Louis Creek trestle to throw rocks at a passing freight. Gondolas, tanker cars...suddenly I saw a group of Mexican hobos lounging in an open box car just as a rock bounced off the car right next to their heads with a CLANG! We fled in a panic, fearful that they were going to jump off and hunt us down.

While the trains were a constant source of amusement and games, there was always an element of danger and death as well. Stories of getting sucked under a fast moving freight turned out to be false, but the story of my granduncle losing an arm when he fell across the path of an oncoming train was true. Once, in the first grade, a chemical leak in a tank car forced us to spend recess indoors, which led to a grand game of school wide dodge ball in the tiny gymnasium. Years later an Amtrack derailed in the Fraser Canyon, resulting in no deaths, but giving us a rare spot on the national news. The worst incident occured in the mid-80’s when a train smashed into a car up at the 4 bar 4 road crossing one frigid winter night. My step dad was a tow truck driver and was one of the first on the scene. They looked everywhere for the body, assuming that it had been jettisoned from the vehicle upon impact, but they simply couldn’t find it. Turns out she was still in the mangled remains of the automobile, dead silent in the midst of a frantic search effort.

Incidents like this were rare, however, and most of the time the trains passed through town without fanfare or disaster, just like they have for the last 100 years. The rails provide a sort of long term calendar for Fraserites to guide their lives by: trains throughout the day and night are like the hours on a clock; the Amtrack is like the rising and setting of the sun (but don’t set your watch by it!); the annual circus train was like a new year’s celebration; and the ski train was the harbinger of winter and hordes of tourists. Longer cycles and stages of life were mirrored by the crews of gandy dancers that would come through twice in a decade to replace the rails, sleeping at the siding in bunkhouse cars next to the bizarre array of machinery unique to the railroad.

The railroad looms large in the history of Fraser, for it brought sawmills, settlers, and civilization to the cold, quiet valley, and led to the very creation of the town itself. These days, for better or for worse, it carries the seemingly endless tons of coal necessary to power our computers, lights and teevees, and will, in the future, surely play a larger role in the transport of both freight and people. Certainly the railroad is big and important, but it’s the small things that have a hold on my heart: the way the rail sinks and flexes as a loaded coal car passes over it; the squeals and squeaks and occasional CLUNK CLUNK CLUNK as one of the flatwheelers passes by; the flashing lights and clanging bells of the crossing gates; the lingering hiss of the rails right after the last car goes by; walking the thousand mile-long balance beam on the way to little league games and elementary school, and, of course, the sound of the whistle at night. Sure, the mountains are the soul of my Fraser, but the train is its beating heart.

Keebirds, Glorious Keebirds

Despite the brief mountain summers, Fraser has had its own little league baseball team since at least the 1920’s. In my day we were called the Keebirds, and the team logo was an igloo with a strange looking bird on top of it. The name came from the sound that this bird would make: “KEE Kee Kee Khrist its cold!”, or so we were told. Our uniforms consisted of a red t-shirt and a red and white cap, usually worn with standard blue jeans. Sometimes we’d tuck our pant legs into our socks in an effort to get that big league look, and eventually the plain shirts came with the Keebird logo, but overall our uniforms were spartan and practical.

But none of this mattered to us, for we just wanted to play baseball. Starting at age 7, our first few seasons were as tee ballers, a variation of coach pitch where the ball was placed on an adjustable rubber apparatus on a stand and the batter just swung away as the umpire and county judge, Larry Peterson, would yell “SOCKO!”. Games were two innings long, and every kid got a chance to bat once each inning. No one sat on the bench, and if the team consisted of 20 kids then every one of them would be out there somewhere waiting to catch a fly ball. For us Fraser kids, home games were on Tuesdays, away games on Thursdays, but no matter where we played, games started at 5 and ended at 6, when the big kids would take the field for 6 innings or 2 hours, whichever came first.

During my first two seasons, home games were played at a makeshift field up the Church’s Park road next to the Morrow’s garage and storage yard. The field was all gravel, with some scattered weeds making up the outfield, and a pine forest serving as the outfield wall. No dugouts or fancy fences either, just splintery wooden benches and a backstop, with splintery red bleachers for the parents. In 1979, I became eligible halfway through the season when I turned seven, and during the last game, part of a tournament, I hit my very first homerun. Really it was a comedy of errors, and all I remember is running into home where all my teammates were cheering for me. I don’t think I even knew what happened, cause the exact rules of the game were still a bit confusing to me.

Next season I was ready. This was the last year at the Morrow’s field, the dry and dusty diamond made even more so by a drought which caused a trio of large forest fires around the state, creating some amazing blood red sunsets. The big town back then was Granby, and they had enough kids to field two teams, the Warriors and the Lions. The Warriors were always hard to beat. They had a reputation for being bad asses, for in addition to their banana seated bicycle gangs and fancy sod field, they had an intimidating pitcher named Kevin Schmuck. He wore clean white cleats and could throw a mean fastball, a daunting combination that made me glad to still be a mere teeballer. The Lions, on the other hand, were never very good, and in the most memorable game of the season we beat them at home in the final inning, just before dark. This was little league, so we teeballers were mere spectators, but I remember the lump in my throat when the homerun was hit and we won the game. Elation! Then Glenn Smith, a pillar of our youthful community and an all-star center fielder, walked into the midst of the celebration and said “time for a little cheer”, so we chanted in unison:

TWO FOUR SIX EIGHT WHO DO WE APPRECIATE?

LIONS LIONS LIONS!

It felt like something right out of a movie, maybe the Bad News Bears, and it was the first and last time I ever saw it happen.

The next season was a real milestone, for we now had a brand new field right next to the brand new school, complete with cinderblock dugouts and a concession stand. In addition to the new field, this season was to be 20 games long instead of the usual 10, the only time this happened, and our shirts and hats now had the actual Keebird logo on them, icing on the cake of a grand summer of baseball.

This was the final season for some of the big names, such as Jeremy Wheeler, Glenn Smith, and Mark Eichler, and all three of them hit over the fence grand slams that season. It was a community affair, as parents cheered from the bleachers or sat in cars along right field, honking their horns with each home team hit and hoping no foul ball would take out their windshield. Not to mention old Tater rolling by real slow in his blue truck for a look-see. A crew of moms, especially Iva Tucker and Donna Morrow, worked the concession stand, selling hotdogs, sodas and candy, and awarding all Fraser home run hitters a free dog. Bill Edwards was the head coach, with his bully son Mike and Greg Tucker coaching teeball, but a new kid from New York was now on the team, and his mom Pam became our real coach, organizing 3 practices a week and eventually guiding us to a championship.

This was my last year of teeball, and since we had too few kids to make a team, the league made an exception and a slew of 6 year olds got to play for us...Buchheister, Shelton, Lorton, Childers, pretty much every boy from my sister’s first grade class. This put a lot of pressure on the more experienced teeballers, but that was fine, cause we now got to practice with the heavy hitters and even got to play an inning or two of regulation ball. Greg Smith and Darrell Woods wanted to become pitchers, but I decided I wanted to be a catcher, and on practice days I would bury my pint-sized self in the bulky gear and step behind home plate, barely able to see, and rarely able to throw to second base.

The super extended season came down to the last game, the Keebirds against the Badgers, in Grand Lake. Despite their baby blue uniforms, the Badgers were even more bad ass than the Warriors. Their names were printed on the backs of their shirts, and they even wore the black face paint under their eyes like the pros. To make things worse, two of the meanest of Fraser’s bullies had moved to Grand Lake and were now Badgers, which made the team all the more intimidating. BUT WE BEAT THEM! Or tied them anyway, in a game in which I had my first little league at bat (grounded out). In the end we tied them for league champions, and celebrated with a big party at the balcony house, complete with unlimited free alpine slide rides for all, and team pictures too.

The next season was anything but stellar, as we struggled with a new coach and a small team. Ronnie Morrow and Marc Tucker were playing again, part of a long tradition of Tuckers and Morrows playing for Fraser. Jessie Smith and Justin Sharp were on the roster as well. Chris Berquist and I traded off as catcher, with Jayce Elliston and Larry Muskoff as starting pitchers and Darrell and Greg in the nonexistent bullpen. We also had a girl pitcher that year named Tami Olson, who schooled the scoffing Badger boys by striking them out. I dated Muskoff’s sister Kristin that summer, but she was an experienced Jr. High girl who dumped me when I showed more interest in bikes and games than smooches. One memorable moment of this summer, 1982, was when she got a trampoline for her birthday. Most every kid in town showed up to partake in the moment, and we bounced and listened to a top 40 countdown that culminated with the Go Go’s at number 1.

One of our last games of the season was scheduled to take place in Walden, a remote town a couple hours north of Fraser. A carload of kids and two moms showed up at the field but it was utterly deserted. Turns out it was haying season, and every available hand was out in the golden meadows helping with the one harvest of the year. On the way back we stopped to watch some ranchers stack hay with a team of horses, the old fashioned way.

The next baseball season was our best, for we were all veterans and were ready to win. Hoot Maynard’s uncle was the official coach this year, although his assistants Gregg Tucker and Chad Burnbeck were the real leaders. Both of them were 16 or 17, drove muscle cars, and liked to remind us that if a shortstop stands in the base path then you have a right to run him down, football style. They also believed in reinforcing the classic “get in front of the ball, its not gonna hurt you.” Which we knew to be false, since a ground ball hit by Holgar, a German exchange student, had knocked out Glenn’s front teeth just a year earlier. We lost our first game to the Warriors in Granby, but we went on to win the next 9 in a row to take the title. We were tough this season, starting our winning streak against the Badgers in Grand Lake: last inning, last batter, all we had to do was get one more out and we win. I called a time out and trekked out to the mound in my oversized gear to confer with the pitcher, a big guy with a big arm, Wade Weinel. The Badger’s final batter was a rookie of small stature, obviously nervous to be facing such a daunting pitcher. I told Wade to throw it as hard as he could and just a wee bit inside for the psychological edge. The whole team at once, as usual, trying to throw off the hitter’s concentration with the mantra of “HEY BATTER BATTER BATTER HEY BATTER BATTER SWING!” That poor kid never had a chance, as Wade’s fastball was a blur that walloped my catcher’s glove and made my hand hurt for days. Later that season, we whipped ‘em again, 29 to 3 in a rainy game that turned our clay field into a gumbo quagmire. We celebrated at the Dairy King (now the Thai place) with ice cream and root beer for all.

The crucial game came midway through the season, at home against the Warriors, the only team that had beaten us. It was late in the game, and we were down by 2 with 2 men on base...Rally caps on, adrenaline on high, we tormented their pitcher from the dugout with taunts and plays on his name: “Come on Patty, you can do better than that!”. I took the plate, let a few pitches pass by, and then WHACKED a line drive right over the outstretched glove of the first baseman for a triple that tied up the game, which we went on to win. This was the finest moment of my baseball career.

We finished the season with a win in Hot Sulphur and a 9 and 1 record, the best of any team I ever played with. After the game, the Rec. District cronies demanded that we turn in our uniforms, but there was NO WAY we were going to do that. Keeping your shirt and hat was a rite of passage, especially after a championship season, and nobody was going to tell us otherwise.

Unfortunately, this incident with the rec. district was a harbinger of things to come, and my final season would be marred by a yuppie takeover. Back then there was no pony league or high school baseball, so when you got too old for little league then you could pretty much hang up your glove. This was to be the final year for a lot of us, including Emur Jensen, Darrell Woods, Justin Sharp, Greg Smith, Marc Tucker, and myself. Gregg Tucker and Chad Burnbeck were the only coaches this year, which meant lots of chaos and fun, especially at practice. We tried to roll their car over once, with them in it, but they saved themselves by throwing lit firecrackers at us. Although I wanted it to be a stellar season, I knew before it started that we would lose most of our games. Such was the Fraser curse: a banner year followed by a summer of losses. Not to mention that half of our championship team from the previous year were now teenagers and ineligible. Another sign that things weren’t quite right occurred after one of the first practices of the season. A few of us were just messing around on the field, and as Greg Smith caught a ball deep in center field I yelled for him to bring it on home. So he threw it with all his might...which was a bit too much, as I watched the hard rawhide pill arc high into the sky and then drop, but not before it cleared the whole backstop and hit some lady right on the side of the head. Just a slight concussion thankfully, for I’m sure it could have easily killed her.

We were halfway into a losing season when a group of concerned parents decided there were too many “four letter words” being spoken at practice, and that we just weren’t getting enough discipline and supervision. These were the same folks who tried to get us to return our uniforms the year before: rich folks from the ski area who didn’t want their kids exposed to any red neck offspring with potty mouths. So they forced the young coaches out, and the oldest of us quit the team in protest, never to play another game of baseball again. This was more than just replacing coaches however, for it symbolized the changes that had been creeping up on the town for years. Hippies turned Saab driving real estate agents were supplanting the working class families who had been there for generations, and Jazzercize was replacing cases of Coors.

Fraser now has a nice new sports complex, with multiple ball fields, volleyball courts, and even an in-line hockey rink. The fields are well manicured sod, the dugouts are quite nice, and it’s unlikely that a grounder will bounce off a hidden chunk of granite and knock some kid’s teeth out. Times have indeed changed, and while in my eyes it seems that something is missing, I’m sure that the magic is still the same as it ever was: the color of the summer sky beyond centerfield as the sun gets low and the score is tied; the satisfying feel of bat hitting ball; the thrill of the bike ride home following a hard game, ball glove on the handlebars, the chilly night air soothing sunburned arms. Kids will always be kids, and summer evenings of baseball will always be timeless, but I’m glad my baseball daze took place on a gravel field.

But none of this mattered to us, for we just wanted to play baseball. Starting at age 7, our first few seasons were as tee ballers, a variation of coach pitch where the ball was placed on an adjustable rubber apparatus on a stand and the batter just swung away as the umpire and county judge, Larry Peterson, would yell “SOCKO!”. Games were two innings long, and every kid got a chance to bat once each inning. No one sat on the bench, and if the team consisted of 20 kids then every one of them would be out there somewhere waiting to catch a fly ball. For us Fraser kids, home games were on Tuesdays, away games on Thursdays, but no matter where we played, games started at 5 and ended at 6, when the big kids would take the field for 6 innings or 2 hours, whichever came first.

During my first two seasons, home games were played at a makeshift field up the Church’s Park road next to the Morrow’s garage and storage yard. The field was all gravel, with some scattered weeds making up the outfield, and a pine forest serving as the outfield wall. No dugouts or fancy fences either, just splintery wooden benches and a backstop, with splintery red bleachers for the parents. In 1979, I became eligible halfway through the season when I turned seven, and during the last game, part of a tournament, I hit my very first homerun. Really it was a comedy of errors, and all I remember is running into home where all my teammates were cheering for me. I don’t think I even knew what happened, cause the exact rules of the game were still a bit confusing to me.

Next season I was ready. This was the last year at the Morrow’s field, the dry and dusty diamond made even more so by a drought which caused a trio of large forest fires around the state, creating some amazing blood red sunsets. The big town back then was Granby, and they had enough kids to field two teams, the Warriors and the Lions. The Warriors were always hard to beat. They had a reputation for being bad asses, for in addition to their banana seated bicycle gangs and fancy sod field, they had an intimidating pitcher named Kevin Schmuck. He wore clean white cleats and could throw a mean fastball, a daunting combination that made me glad to still be a mere teeballer. The Lions, on the other hand, were never very good, and in the most memorable game of the season we beat them at home in the final inning, just before dark. This was little league, so we teeballers were mere spectators, but I remember the lump in my throat when the homerun was hit and we won the game. Elation! Then Glenn Smith, a pillar of our youthful community and an all-star center fielder, walked into the midst of the celebration and said “time for a little cheer”, so we chanted in unison:

TWO FOUR SIX EIGHT WHO DO WE APPRECIATE?

LIONS LIONS LIONS!

It felt like something right out of a movie, maybe the Bad News Bears, and it was the first and last time I ever saw it happen.

The next season was a real milestone, for we now had a brand new field right next to the brand new school, complete with cinderblock dugouts and a concession stand. In addition to the new field, this season was to be 20 games long instead of the usual 10, the only time this happened, and our shirts and hats now had the actual Keebird logo on them, icing on the cake of a grand summer of baseball.

This was the final season for some of the big names, such as Jeremy Wheeler, Glenn Smith, and Mark Eichler, and all three of them hit over the fence grand slams that season. It was a community affair, as parents cheered from the bleachers or sat in cars along right field, honking their horns with each home team hit and hoping no foul ball would take out their windshield. Not to mention old Tater rolling by real slow in his blue truck for a look-see. A crew of moms, especially Iva Tucker and Donna Morrow, worked the concession stand, selling hotdogs, sodas and candy, and awarding all Fraser home run hitters a free dog. Bill Edwards was the head coach, with his bully son Mike and Greg Tucker coaching teeball, but a new kid from New York was now on the team, and his mom Pam became our real coach, organizing 3 practices a week and eventually guiding us to a championship.

This was my last year of teeball, and since we had too few kids to make a team, the league made an exception and a slew of 6 year olds got to play for us...Buchheister, Shelton, Lorton, Childers, pretty much every boy from my sister’s first grade class. This put a lot of pressure on the more experienced teeballers, but that was fine, cause we now got to practice with the heavy hitters and even got to play an inning or two of regulation ball. Greg Smith and Darrell Woods wanted to become pitchers, but I decided I wanted to be a catcher, and on practice days I would bury my pint-sized self in the bulky gear and step behind home plate, barely able to see, and rarely able to throw to second base.

The super extended season came down to the last game, the Keebirds against the Badgers, in Grand Lake. Despite their baby blue uniforms, the Badgers were even more bad ass than the Warriors. Their names were printed on the backs of their shirts, and they even wore the black face paint under their eyes like the pros. To make things worse, two of the meanest of Fraser’s bullies had moved to Grand Lake and were now Badgers, which made the team all the more intimidating. BUT WE BEAT THEM! Or tied them anyway, in a game in which I had my first little league at bat (grounded out). In the end we tied them for league champions, and celebrated with a big party at the balcony house, complete with unlimited free alpine slide rides for all, and team pictures too.

The next season was anything but stellar, as we struggled with a new coach and a small team. Ronnie Morrow and Marc Tucker were playing again, part of a long tradition of Tuckers and Morrows playing for Fraser. Jessie Smith and Justin Sharp were on the roster as well. Chris Berquist and I traded off as catcher, with Jayce Elliston and Larry Muskoff as starting pitchers and Darrell and Greg in the nonexistent bullpen. We also had a girl pitcher that year named Tami Olson, who schooled the scoffing Badger boys by striking them out. I dated Muskoff’s sister Kristin that summer, but she was an experienced Jr. High girl who dumped me when I showed more interest in bikes and games than smooches. One memorable moment of this summer, 1982, was when she got a trampoline for her birthday. Most every kid in town showed up to partake in the moment, and we bounced and listened to a top 40 countdown that culminated with the Go Go’s at number 1.

One of our last games of the season was scheduled to take place in Walden, a remote town a couple hours north of Fraser. A carload of kids and two moms showed up at the field but it was utterly deserted. Turns out it was haying season, and every available hand was out in the golden meadows helping with the one harvest of the year. On the way back we stopped to watch some ranchers stack hay with a team of horses, the old fashioned way.

The next baseball season was our best, for we were all veterans and were ready to win. Hoot Maynard’s uncle was the official coach this year, although his assistants Gregg Tucker and Chad Burnbeck were the real leaders. Both of them were 16 or 17, drove muscle cars, and liked to remind us that if a shortstop stands in the base path then you have a right to run him down, football style. They also believed in reinforcing the classic “get in front of the ball, its not gonna hurt you.” Which we knew to be false, since a ground ball hit by Holgar, a German exchange student, had knocked out Glenn’s front teeth just a year earlier. We lost our first game to the Warriors in Granby, but we went on to win the next 9 in a row to take the title. We were tough this season, starting our winning streak against the Badgers in Grand Lake: last inning, last batter, all we had to do was get one more out and we win. I called a time out and trekked out to the mound in my oversized gear to confer with the pitcher, a big guy with a big arm, Wade Weinel. The Badger’s final batter was a rookie of small stature, obviously nervous to be facing such a daunting pitcher. I told Wade to throw it as hard as he could and just a wee bit inside for the psychological edge. The whole team at once, as usual, trying to throw off the hitter’s concentration with the mantra of “HEY BATTER BATTER BATTER HEY BATTER BATTER SWING!” That poor kid never had a chance, as Wade’s fastball was a blur that walloped my catcher’s glove and made my hand hurt for days. Later that season, we whipped ‘em again, 29 to 3 in a rainy game that turned our clay field into a gumbo quagmire. We celebrated at the Dairy King (now the Thai place) with ice cream and root beer for all.

The crucial game came midway through the season, at home against the Warriors, the only team that had beaten us. It was late in the game, and we were down by 2 with 2 men on base...Rally caps on, adrenaline on high, we tormented their pitcher from the dugout with taunts and plays on his name: “Come on Patty, you can do better than that!”. I took the plate, let a few pitches pass by, and then WHACKED a line drive right over the outstretched glove of the first baseman for a triple that tied up the game, which we went on to win. This was the finest moment of my baseball career.

We finished the season with a win in Hot Sulphur and a 9 and 1 record, the best of any team I ever played with. After the game, the Rec. District cronies demanded that we turn in our uniforms, but there was NO WAY we were going to do that. Keeping your shirt and hat was a rite of passage, especially after a championship season, and nobody was going to tell us otherwise.

Unfortunately, this incident with the rec. district was a harbinger of things to come, and my final season would be marred by a yuppie takeover. Back then there was no pony league or high school baseball, so when you got too old for little league then you could pretty much hang up your glove. This was to be the final year for a lot of us, including Emur Jensen, Darrell Woods, Justin Sharp, Greg Smith, Marc Tucker, and myself. Gregg Tucker and Chad Burnbeck were the only coaches this year, which meant lots of chaos and fun, especially at practice. We tried to roll their car over once, with them in it, but they saved themselves by throwing lit firecrackers at us. Although I wanted it to be a stellar season, I knew before it started that we would lose most of our games. Such was the Fraser curse: a banner year followed by a summer of losses. Not to mention that half of our championship team from the previous year were now teenagers and ineligible. Another sign that things weren’t quite right occurred after one of the first practices of the season. A few of us were just messing around on the field, and as Greg Smith caught a ball deep in center field I yelled for him to bring it on home. So he threw it with all his might...which was a bit too much, as I watched the hard rawhide pill arc high into the sky and then drop, but not before it cleared the whole backstop and hit some lady right on the side of the head. Just a slight concussion thankfully, for I’m sure it could have easily killed her.

We were halfway into a losing season when a group of concerned parents decided there were too many “four letter words” being spoken at practice, and that we just weren’t getting enough discipline and supervision. These were the same folks who tried to get us to return our uniforms the year before: rich folks from the ski area who didn’t want their kids exposed to any red neck offspring with potty mouths. So they forced the young coaches out, and the oldest of us quit the team in protest, never to play another game of baseball again. This was more than just replacing coaches however, for it symbolized the changes that had been creeping up on the town for years. Hippies turned Saab driving real estate agents were supplanting the working class families who had been there for generations, and Jazzercize was replacing cases of Coors.

Fraser now has a nice new sports complex, with multiple ball fields, volleyball courts, and even an in-line hockey rink. The fields are well manicured sod, the dugouts are quite nice, and it’s unlikely that a grounder will bounce off a hidden chunk of granite and knock some kid’s teeth out. Times have indeed changed, and while in my eyes it seems that something is missing, I’m sure that the magic is still the same as it ever was: the color of the summer sky beyond centerfield as the sun gets low and the score is tied; the satisfying feel of bat hitting ball; the thrill of the bike ride home following a hard game, ball glove on the handlebars, the chilly night air soothing sunburned arms. Kids will always be kids, and summer evenings of baseball will always be timeless, but I’m glad my baseball daze took place on a gravel field.

A True Mountain Woman: Elsie Josephine Clayton

This was published in the Mountain Gazette in early 2006.

The deceased: A true mountain woman, Elsie J. Clayton.

Born: January 2, 1911 Died: November 13, 2005 Cause of death: Old-fashioned old age.

She entered this world during one of the coldest weeks of the year. Chimney smoke from the cabin by the railroad tracks rose straight into the frigid air, and a young couple gave thanks for the healthy birth of their firstborn child: Elsa Josephina Goranson.

A mountain childhood: churn the butter, stoke the perpetual fire in the woodstove, pile three on a horse and ride into the woods for a picnic, tend to your younger siblings while mother and father scratch a living out of this frozen valley.Watch through the window as Dad trudges through mud or drifting snow to the barn.Watch the mountains turn pink with alpenglow.Watch the gales blow banners of snow off Byers Peak. On Christmas, the house stunk of lutefisk and resounded with the songs and laughter of Swedes, some of them drunk, all of them misty eyed for the distant homeland they had left just a few years before.

Eleven years of school in a one-room schoolhouse, then graduation and a train ride over Rollins Pass to live the wild life of a bachelorette in the big city of Denver. 1927, sixteen years old, taking the streetcar down to Curtis Street for the bright lights of the theater district, even riding in the motorcar of a young man from Pine a time or two. Back home for a visit, and a date with a gambling, drinking, wild and handsome young Okie: a sleigh ride down valley to a dance in Tabernash, that riproaring roundhouse town.

Marriage soon makes them Chuck and Elsie Clayton. A season in Breckenridge where Chuck works in a mine, a season in Lyons working in a sawmill, then back up to the cold Fraser Valley for the rest of their lives.

1933: open up a café and bar on the new U.S. Highway 40. The next four decades are a blur of 16-hour workdays, rollicking New Year’s Eve parties, and a long medley of songs on the jukebox. Hunters stop in to celebrate the gutted elk strapped to the hood of their Plymouth. Truckers headed for Salt Lake City or San Francisco pause for ham and eggs and a cup of coffee. The valley’s first skiers order up burgers and beer. President Eisenhower even comes to town, and Elsie handdelivers two of her signature cherry pies to the leader of the free world.

Retired, 1971. Start a journal of the days’ events: A visitor from out of town, an illness in the family, 55 below zero on the morning thermometer, three feet of spring snow. Get a library card and read the first of thousands and thousands of books. Michener’s “Centennial” was her favorite. Take drives in the woods, pick raspberries, make jam. Road trips to visit friends and family scattered across the Western states. Coddle the grandkids. The great-grandkids. The great-great-grandkids. Watch the generations come and go.

Chuck dies, a tumble down the courthouse steps after securing one of those goddamn building permits to fix his roof. 71 years of marriage suddenly ends, and the kids wonder how she’ll handle it. Sadness. Grief. An empty place inside that nothing will ever fill. But she clears her closet of his clothes and moves on to the next chapter of life. Trips to the cemetery always bring tears, but back at home, a glass of whiskey soothes 90- year-old nerves, and Elsie says it’s time for a game of dominos.

Ninety-four winters in the “Icebox of the Nation,” much of it spent sitting at a kitchen table, sipping black coffee and peering out the window as waves of change came to the valley. She remembers when the paved highway was a muddy wagon road. She listened to static on the town’s first radio at Carlson’s pool hall. She marveled at the flip-of-the-switch electric lights, basked in the easy warmth of the first gas heat, and was glad when a fancy machine made the washboard obsolete. Her first phone number was 5. She watched from afar as the long clear cuts of ski runs appeared on the mountainside at Winter Park, heard carpenters hammering on the first condominiums and listened as loggers sat on barstools and grumbled about the slow decline of the sawmill. Boom and bust. Boom and bust. Boom and bust. Only the mountains stayed the same.

Despite these experiences, Elsie didn’t philosophize much. Why speculate about an afterlife when there are babies to hold and long conversations to be had? To Elsie, the Holy Grail was a pot of hot coffee, and the reason for our earthly existence was to eat a slice of peach pie right out of the oven. This life is enough.

On the night of November 12, 2005, Elsie said she was sleepy and retired early. She climbed into her own bed, in her own home, a half-mile from the spot where she had been born. Sometime after midnight, she passed on to whatever comes next. That night, a sideways blowing blizzard roared into the Fraser Valley, bringing whiteout conditions and enough snow to cause an early season avalanche that closed Berthoud Pass. On the morning of her funeral, the mercury dropped well below zero. A few hours later, a coal train whistled lonesome during the eulogy.

This town will never be the same.

Fairy Tale Ending

My sweetheart had just gotten a halfway real job and needed some new clothes, so we drove down to the big city of Santa Fe. Passing up our usual foray into the faux adobe district of art and green chile, we rolled along a busy auto strip past faux New England chowder houses and mansard roofed burger joints to an Old Navy store. As she tried on outfits, I browsed the men’s section, amazed at what I saw: The clothes they were selling were a lot like the ones I was wearing. For the first time in my life, I was in style.

Indeed, the shelves were stacked with sweatshop replicas of clothing worn in bars and on job sites across the Rockies. There were imitation Carhartts, pre-frayed around the knees and hems for that working-class look. Thin and light, they wouldn’t make it through a single day of hard labor, but they sure did look cool. So did the olive-green cargo pants, the kind with the big side pockets I had been getting at army surplus stores since I was a teen. Best of all were the mesh baseball caps emblazoned with the pre-faded image of a deer, an orange sunset, and the words “Buck Mesa, Colorado.” It looked like a vintage hat, a rarity from the ’70s. But unlike the Kenworth hat my uncle gave me when I was eight, this was made in Bangladesh, and there were dozens of them for sale. And if there’s a Buck Mesa in Colorado, I’ve never heard of it.

While it would be easy to shrug all this off as just the latest in meaningless fashion, the fact that a big-name national chain store was prominently featuring the tough and rugged “mountain look” is indicative of something deeper. It reveals a change in our national myth — Colorado as the epitome of cool.

It wasn’t always this way. In 1987, my family fled our recession- plagued Colorado hometown for the promise of San Diego, a city in the midst of a Cold War military-industrial-complex boom. As an impressionable 14-year-old who had watched way too much television, I was saturated with the archetypes of Southern California coolness: bad ass Top Gun pilots playing beach volleyball and riding sleek Jap motorcycles, rich folks cruising in convertibles on the Pacific Coast Highway ala “L.A. Law”, skateboarders like Tony Hawk and Gator ripping up half pipes, hot chicks with teased hair and skimpy bikinis lying on white sand beaches. Compared to all that, Colorado sucked, and I was excited to get out of my hick mountain town.

Needless to say, Cali wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. My illusions were shaken the moment we descended into a smoggy valley and pulled into the driveway of our new home, a dilapidated rental with “SLAYER” spray painted in blood red on the garage door, an inauspicious omen.

Within three weeks, my bicycle had been stolen, our house had been burglarized, and I had witnessed my first act of city cruelty — kids throwing rocks at a homeless person. It was a far cry from the Club Med I had envisioned. The only sign of paradise was the palm tree in our front yard, drooping lifelessly in the stifling heat.

Where were the girls in bikinis? The beautiful people in fancy cars? They were at the beach, 20 miles and several socioeconomic brackets away, an impossible distance for someone too young to drive. But when we finally visited the fabled beach, it too, was a letdown. The ocean was cold and murky, even in the hottest part of summer, and the sand was covered with flabby tourists and mounds of rotting seaweed surrounded by flies. I was crushed.

Perhaps, my standards were too high, for even the best possible reality would have fallen short of the storybook scene in my imagination. But it wasn’t just me. Southern California had been riding a wave of coolness since the days of Gidget and the Beach Boys, but by 1990 that wave had crested and was about to crash upon the trash-strewn beach (closed until further notice due to fecal contamination). Maybe it was the riots of ’92, or the fires of ’93, or the earthquake of ’94, or the floods of ’95, but somewhere along the way, folks began to see through the façade of eternal sunshine, and So-Cal lost its golden glow. To be sure, plenty of Latino and Asian immigrants still flock to the place, and many Americans will always be lulled by the easy climate, but the secret is out, and the average person on the street knows that Southern California is a sinking ship of rolling blackouts, gridlock-related shootings and runaway sprawl … the epitome of Paradise Lost.

At the same time that So-Cal’s star was fading, Colorful Colorado was sparkling like champagne powder in the morning sun. The sudden explosion of snowboarding and mountain biking, Elway’s back-to-back Super Bowl victories and a brief spurt of feel good environmental consciousness all thrust the state into the national spotlight. By the late-’90s, a glance at the idiot box revealed an America obsessed with what they perceived to be the Rocky Mountain way: big pickups splashing through streams en route to mountaintop campsites, a hapless backcountry skier tumbling down an avalanche chute while Lenny Kravitz sings about how he wants to get away (imagine the hard-charging yuppies who ran out to buy the advertised SUV just because it included a first-aid kit), and, of course, the scantily clad Coors Light girls showing off the state’s majestic peaks. Consumer culture’s love affair with the outdoors — or at least the “outdoor lifestyle” — was soon in full swing, and everybody who was anybody in places like Indiana quickly swapped their Day-glo Quicksilver surf shirts for a North Face fleece and Nike hiking boots. By the new millennium, America’s longstanding California dream (wine on the porch of a bungalow overlooking the ocean sunset) had been replaced by a new Colorado vision — microbrew on a ranchette surrounded by national forest on three sides. Between 1990 and 2003, Colorado’s population jumped from 3.2 to 4.5 million, a net gain nearly equal to the entire populations of Wyoming and Montana combined, with five mountain counties (Summit, Park, Eagle, Teller and San Miguel) doubling in population. In 2005, for the third year in a row, Boulder was rated #1 in the Men’s Journal annual “50 Best Places to Live” article, while Ft. Collins and Buena Vista (!) made Outside magazine’s short list of 18 “New American Dream Towns.” Indeed, while I was writing this, National Public Radio featured a story on String Cheese Incident and hula-hoops, casually dropping the names of Crested Butte and Telluride in the process. Such media exposure lends credence to the “Colorado as Cool” myth, inspiring countless more devout believers to make the mountain pilgrimage.

But as these wide-eyed neophytes roll into storied mountain towns, they’ll quickly learn that these places are unaffordable for all but the jet set or those willing to take a vow of poverty. Some will take that vow, for a season or even a lifetime, but most will end up in the megalopolis along the Front Range where they’ll settle into a 40-hour workaday existence not unlike the one they came to Colorado to escape. The same brown air. The same traffic. The same crime. Quiet desperation with occasional hazy views of distant mountains. By Friday, they’ll be stressed out and ready for a weekend in the High Country, so they’ll pack up the “Avalanche” or “Colorado” or “Tundra” and hit ye old I-70, braving bottleneck traffic jams for some hurried relaxation in yonder hills.

The mountains will be mighty pretty, but there will be some unexpected problems. Fishermen will elbow their way to an open stretch of stream, only to find that massive diversions by the Denver Water Board have dried up entire watersheds. Hunters will wonder if the succulent back strap of that strange acting elk they just shot is safe to eat. Backpackers seeking solitude in the state’s wilderness areas will encounter countless others searching for the same thing, especially in those remote corners rumored to harbor the elusive grizzly. Families who drop a thousand bucks per day on lodging, ski lessons and lift tickets will then be forced to pay just a little bit more to park, not to mention airport prices for cafeteriaquality food at the base.

Sightseers will find former mining towns “restored” to their original mini-mall/real-estate-office status, and once-enchanted ghost towns will be littered with frappucino cups. Indeed, much of this has already come to pass, and every Sunday evening, throngs of weekend warriors head back to the city with maxxed-out credit cards and heavy hearts. Something just doesn’t seem right.

For a while, the millionaires fortunate enough to actually live in the name-brand towns will live a high life of powder and prestige, secure in the knowledge that as they buy and sell parcels of what used to be a ranch, they are absolutely in tune with the zeitgeist of rustic Western living.

They’ll get involved in worthy community projects like banning low-income housing. They’ll fight to make the place more inclusive, lengthening runways at the airport so those with Lear jets can land safely. They might even publish guidebooks to the local back- country, so that all of their neighbors in the new four-season golf “community” can take full advantage of the beautiful scenery.

After a year or two, they’ll claim the coveted status of “local,” even as they disdain the descendants of pioneers who bag their groceries at Safeway. (All of which has already occurred in my childhood stomping ground of Grand County.)

But like ocean waves gradually undermining a cliff-side estate, eventually the realities of mountain life will crash the party of these New Westerners. For starters, as other like-minded trendsetters build homes in the next big place, convoys of dump trucks and heavy equipment will stir up choking clouds of dust (which settles in thick layers in homes occupied only a few weeks each year). Drought will cause golf courses to lose their green luster, and the fairways will turn an unsightly brown. Pine beetles will infest weakened forests, leaving vast stands of dead timber that will be charred (along with a number of “secluded” trophy homes) by fires of epic proportions. This will ruin the pricey views, causing property values to drop and bursting the much inflated real estate bubble.

Worst of all, as these beautiful people drive their Hummers around town, they’ll be forced to endure the sight of brown-skinned migrant workers who magically appear each day to pour concrete and wash dishes, prompting horrified cries about how “the Mexicans are ruining the place!” In 1859, at the behest of unsubstantiated rumors and newspaper headlines, throngs of would-be millionaires rushed to what is now Colorado to pluck easy money out of the streams of gold, only to discover squalid mining camps and tribes of red skinned locals who were none too happy about the sudden changes. Some of these miners stayed, and a select few struck it rich, but many thousands of them (derided as “go backers” by early pro-growth chamber-of-commerce types) returned home bearing tales of disillusionment and a gut feeling that they’d been lied to. Although it may take another 15 years, Colorado will undergo a similar exodus as the quality of life plummets and folks lose faith in the myth of the mountain life. And where will these emigrants go? What part of this great land of ours could possibly be better than the Rockies?